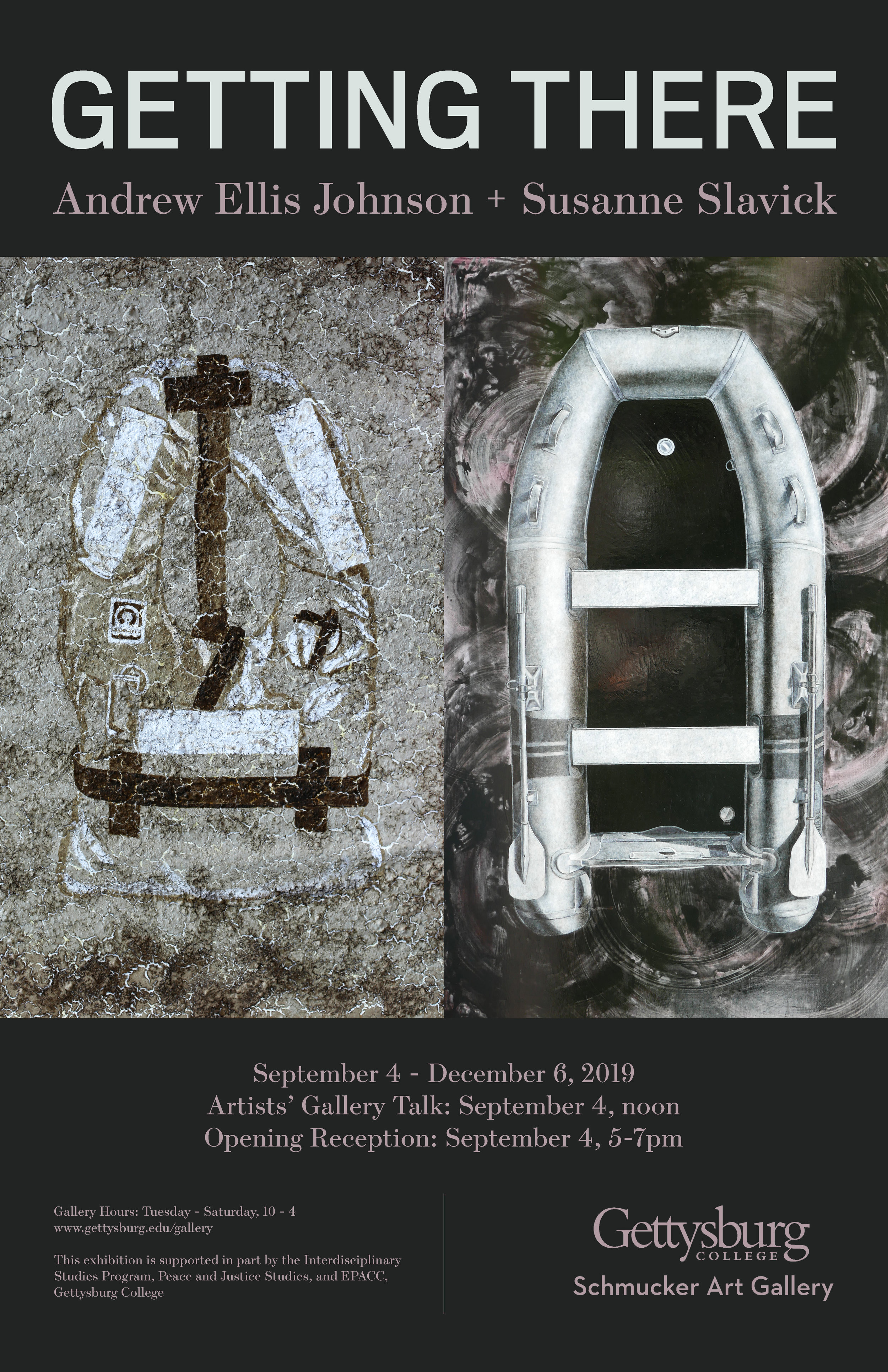

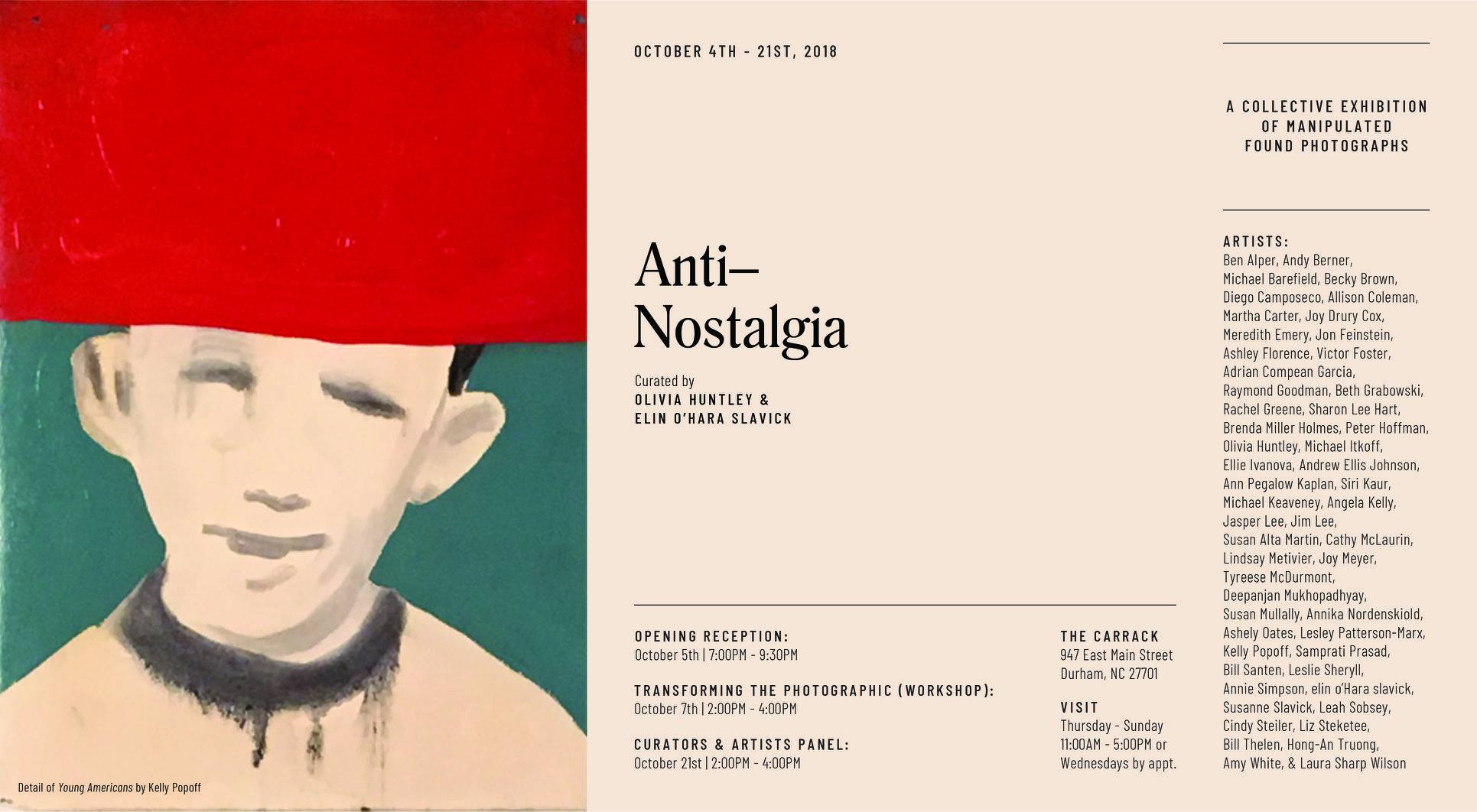

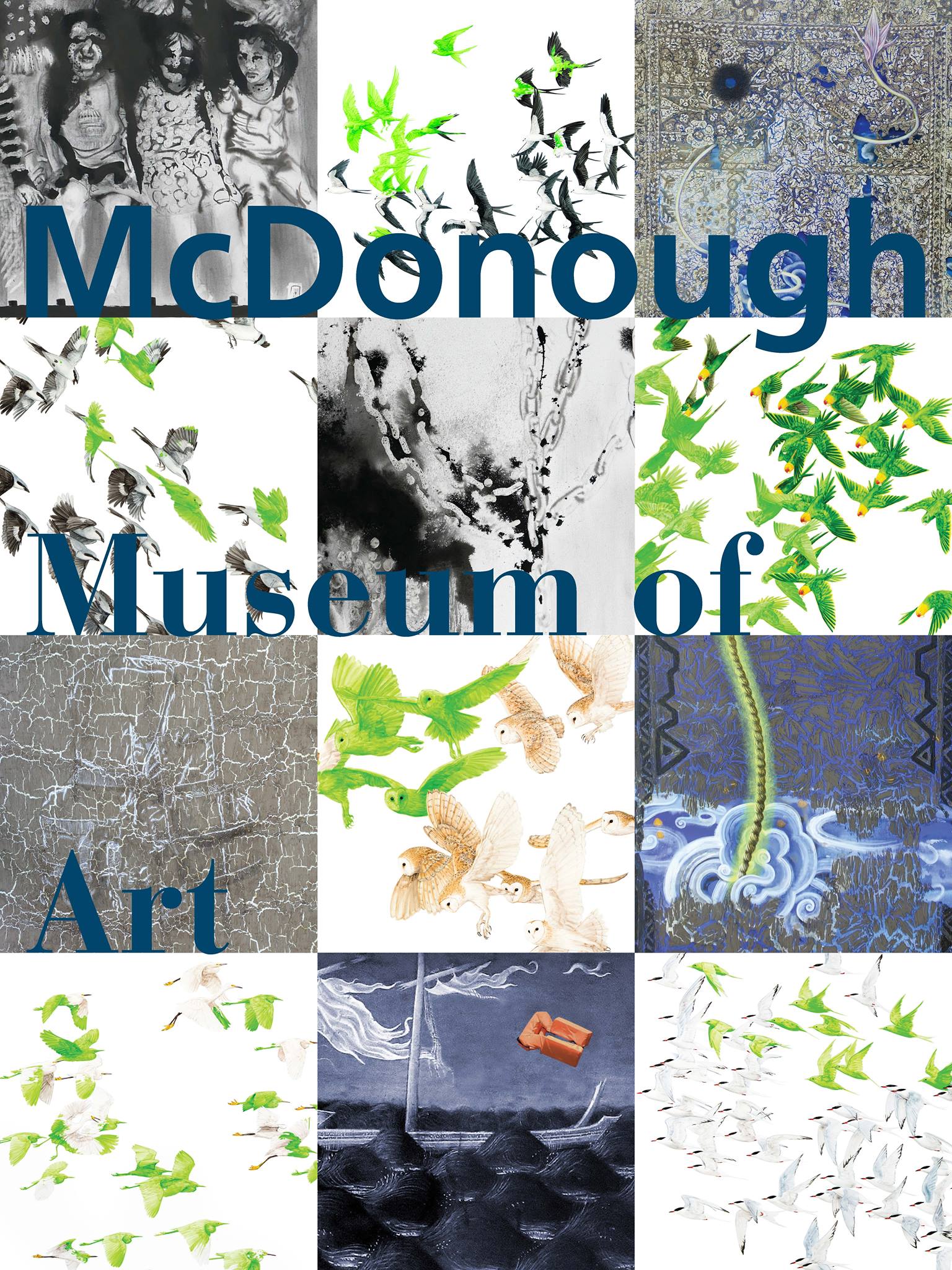

Andrew Ellis Johnson and Susanne Slavick

Schmucker Art Gallery at Gettysburg College

September 4 - December 6, 2019

Catalogue available with poems by David Hernandez, Maria Melendez Kelson, Blas Manuel De Luna, Dunya Mikhail, Prageeta Sharma, Warsan Shire, and Wisława Szymborska; an essay by Suketu Mehta; and texts by Vu Tran.

______________________________________________

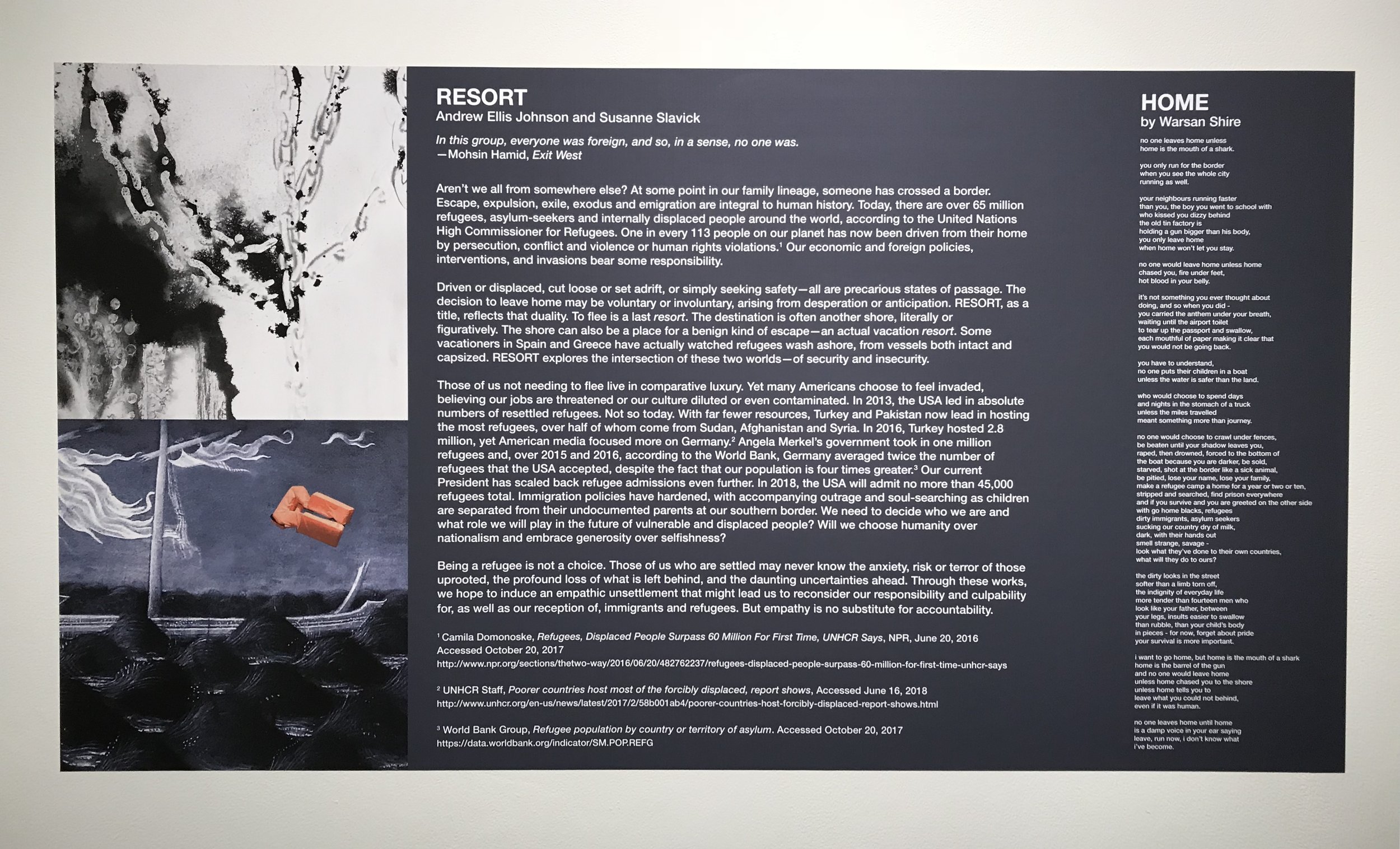

Getting There is aspirational; it implies a destination, marking progress toward some kind of goal. Getting There is a burden, but also a dream of many migrants and refugees. We cannot speak for those in flight, in hiding, and in desperate hope. But we can speak to the contradictory fears and hypocrisies, ignored histories and punitive policies that we as a nation hold and enact here.

We are all from somewhere else. At some point in our family lineage, someone has crossed a border. Escape, expulsion, exile, exodus and emigration are integral to human history. Today, there are over 65 million refugees, asylum-seekers and internally displaced people around the world, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. They are driven from their home by persecution, conflict and violence, or human rights violations.

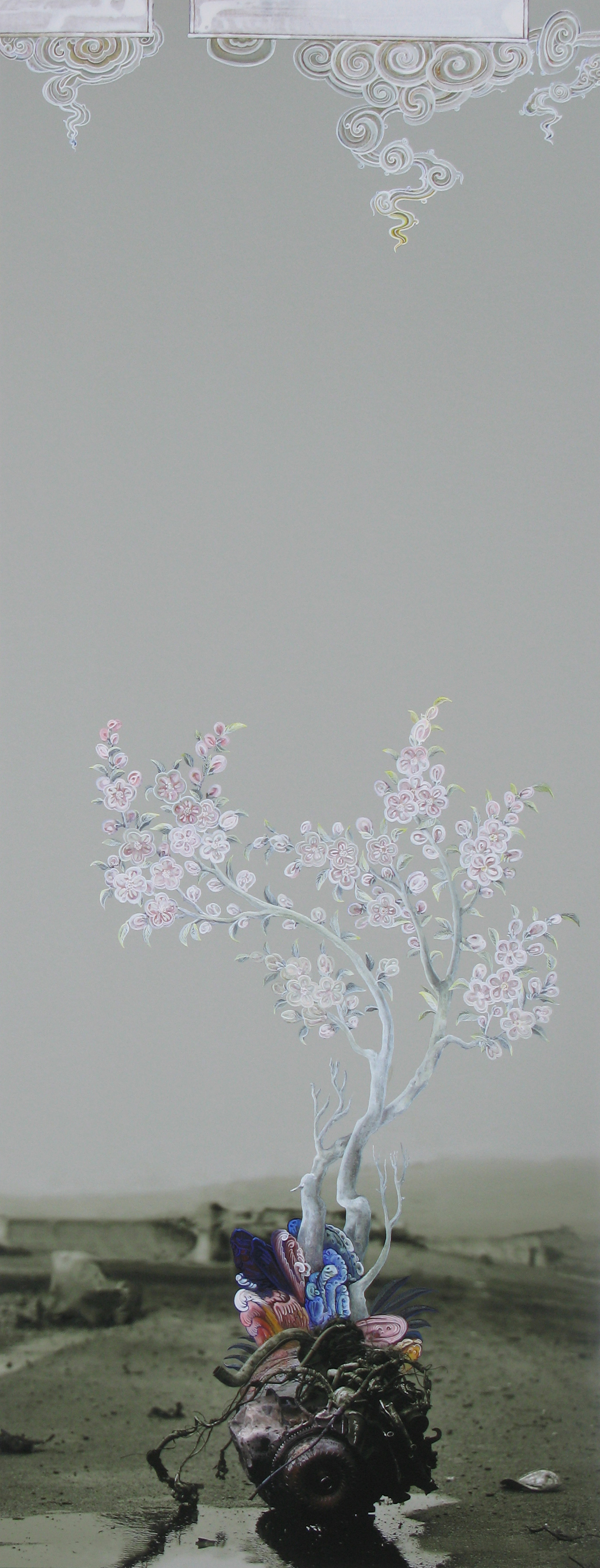

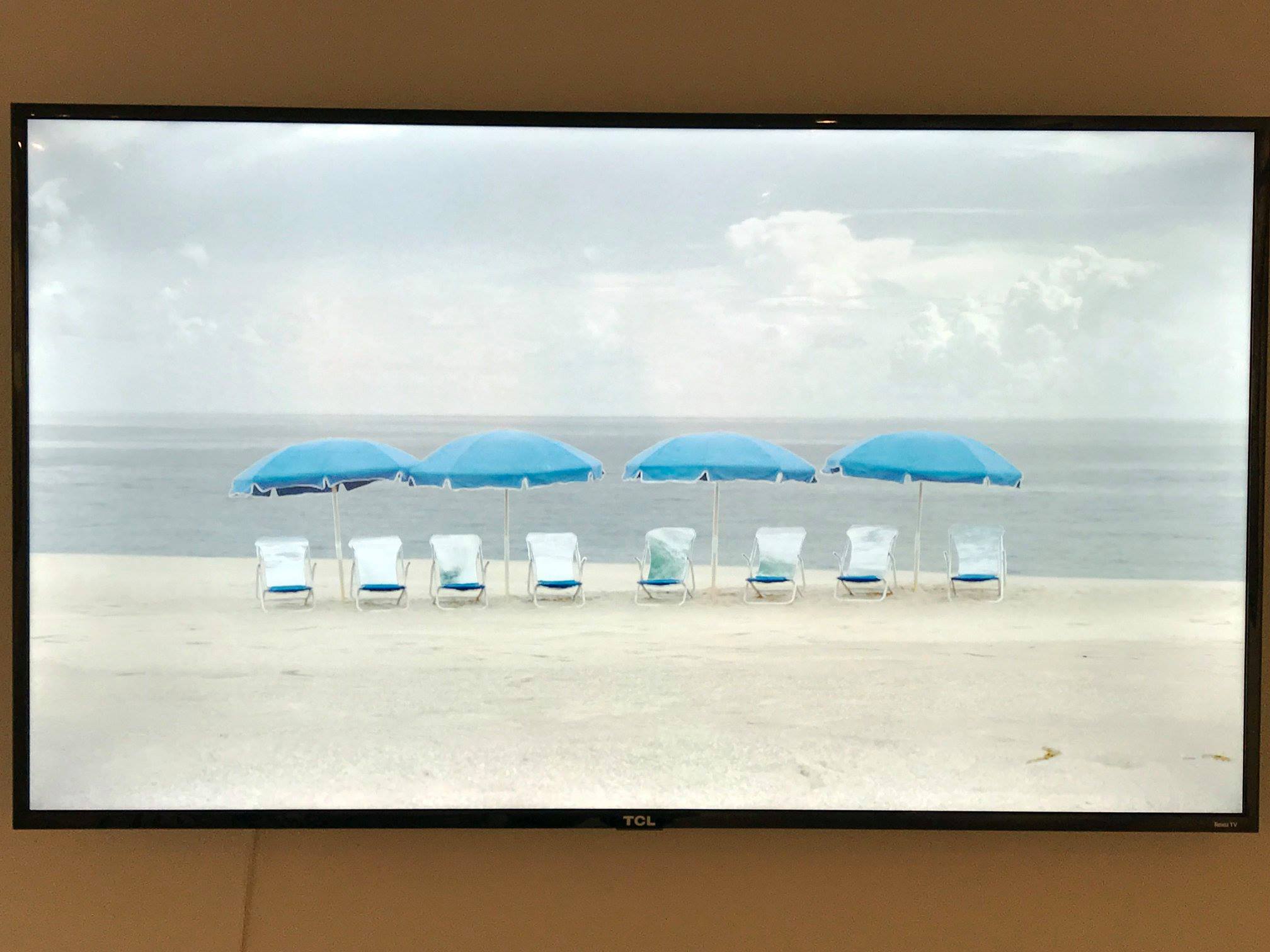

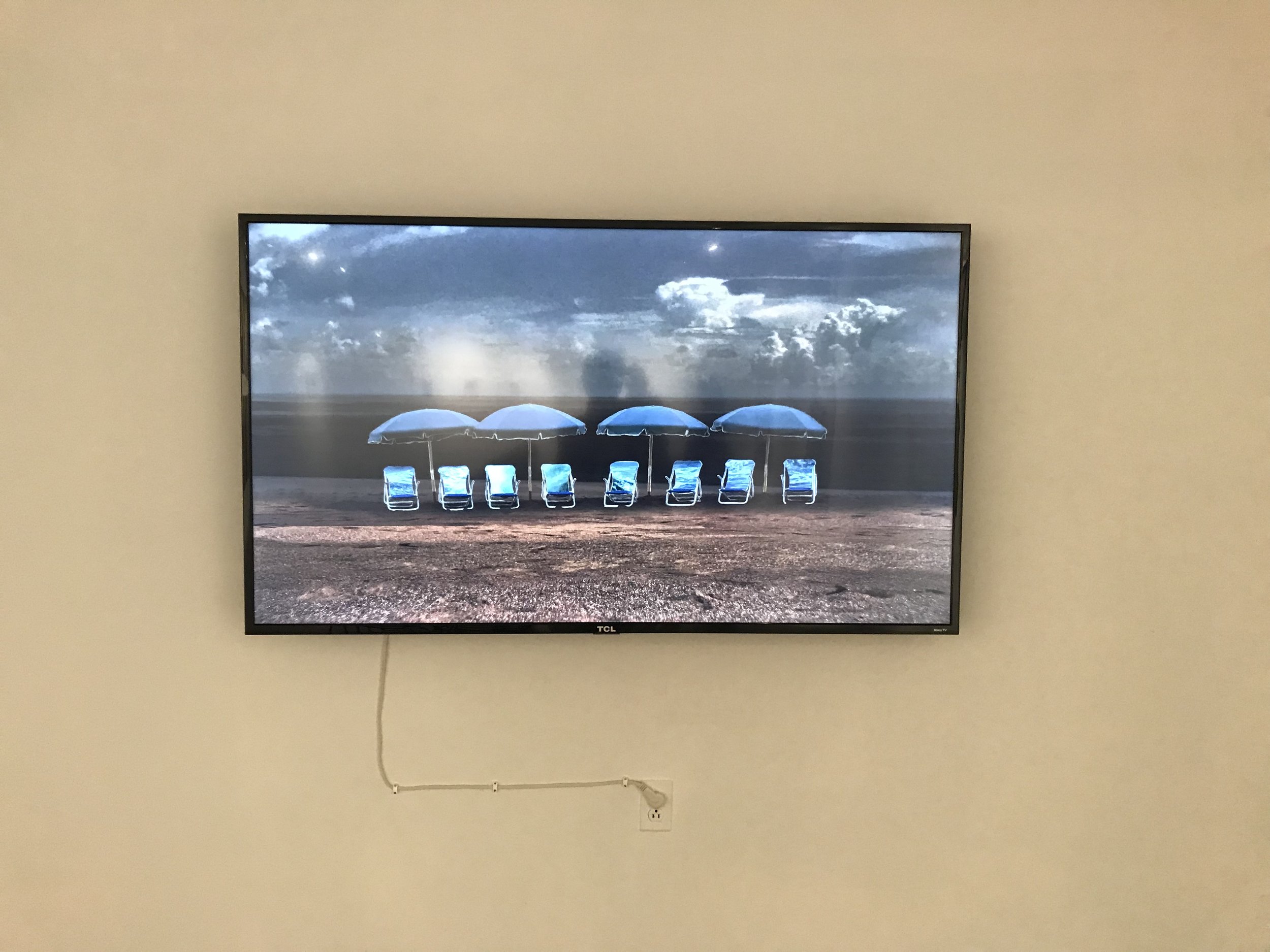

Driven or displaced, cut loose or set adrift, or simply seeking safety—all are precarious states of passage. The decision to leave home may be voluntary or involuntary, arising from desperation or anticipation. Those of us not needing to flee live in comparative luxury. Yet many Americans choose to feel invaded, believing our jobs are threatened or our culture diluted or even contaminated.

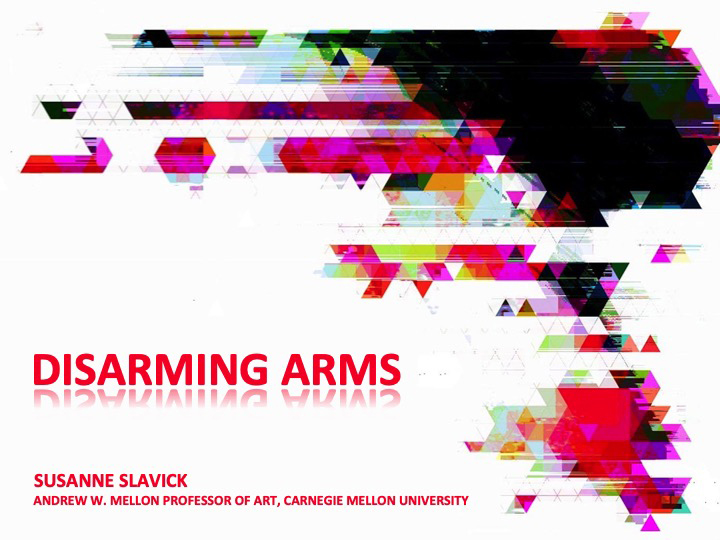

There is real fear and fabricated fear. Both are fierce and ubiquitous. There is the natural fear of the unknown, shared by the vulnerable and those made to feel vulnerable. How are the vanquished so easily demonized into a formidable foe by the rhetoric of demagogues and the media that serves them? Why do alarmist claims of invasion and infestation persist despite the evidence, and despite the abusive history of such language? The “other” is imagined as larger than life—and worse, fueling the dangerous perception that “the thing that is lower than I, makes me bigger.”

Such assumptions and attitudes insist that is not enough to be strong; those perceived as weak and powerless must be punished with deportation, incarceration, and separation from those they love. They must be dehumanized and denied rights to asylum and autonomy. They must remain invisible. The works in Getting There question these manufactured imperatives and expose the consequences of our resentment or fear of “the stranger.”

The USA is a nation of immigrants and used to lead in resettling refugees. Today, with far fewer resources, Turkey and Pakistan now host the most refugees. Our current administration is slashing admissions to its lowest point in 40 years. Immigration policies have hardened, vilifying and incarcerating people who legally seek asylum. Outrage and soul-searching followed the separation of children from parents at the border, but the fury has failed to stop their indefinite detention in unprecedented numbers, against international law.

Being a refugee is not a choice. Those of us who are settled may never know the anxiety, risk or terror of those uprooted, the profound loss of what is left behind, and the daunting uncertainties ahead. Through these works, we explore encounters, intersections and perceptions between radically different worlds—between security and insecurity.

We are moved by images. We are moved by words. We are grateful to novelists, poets, anthropologists and journalists who have informed our projects and whose words we have included or cited. Among them are Jenny Erpenbeck, Lev Golinkin, Eliza Griswold, Mohsin Hamid, David Hernandez, Ali Johar, Maria Melendez Kelson, Jason De León, Blas Manuel De Luna, Suketu Mehta, Dunya Mikhail, Yasser Niksada, Prageeta Sharma, Warsan Shire, Wisława Szymborska, and Vu Tran.

Getting There suggests movement—but more than the literal movement of migrants and refugees. We hope Getting There advances an evolving ethos, a humane reception, an empathic embrace—and movement of our own consciences.